BOGDAN VLĂDUȚĂ. WHEN I PAINT, I KNOW I WILL DIE!

– a visual essay on Van Gogh

Exhibition at Sector 1 Gallery, Bucharest, Romania

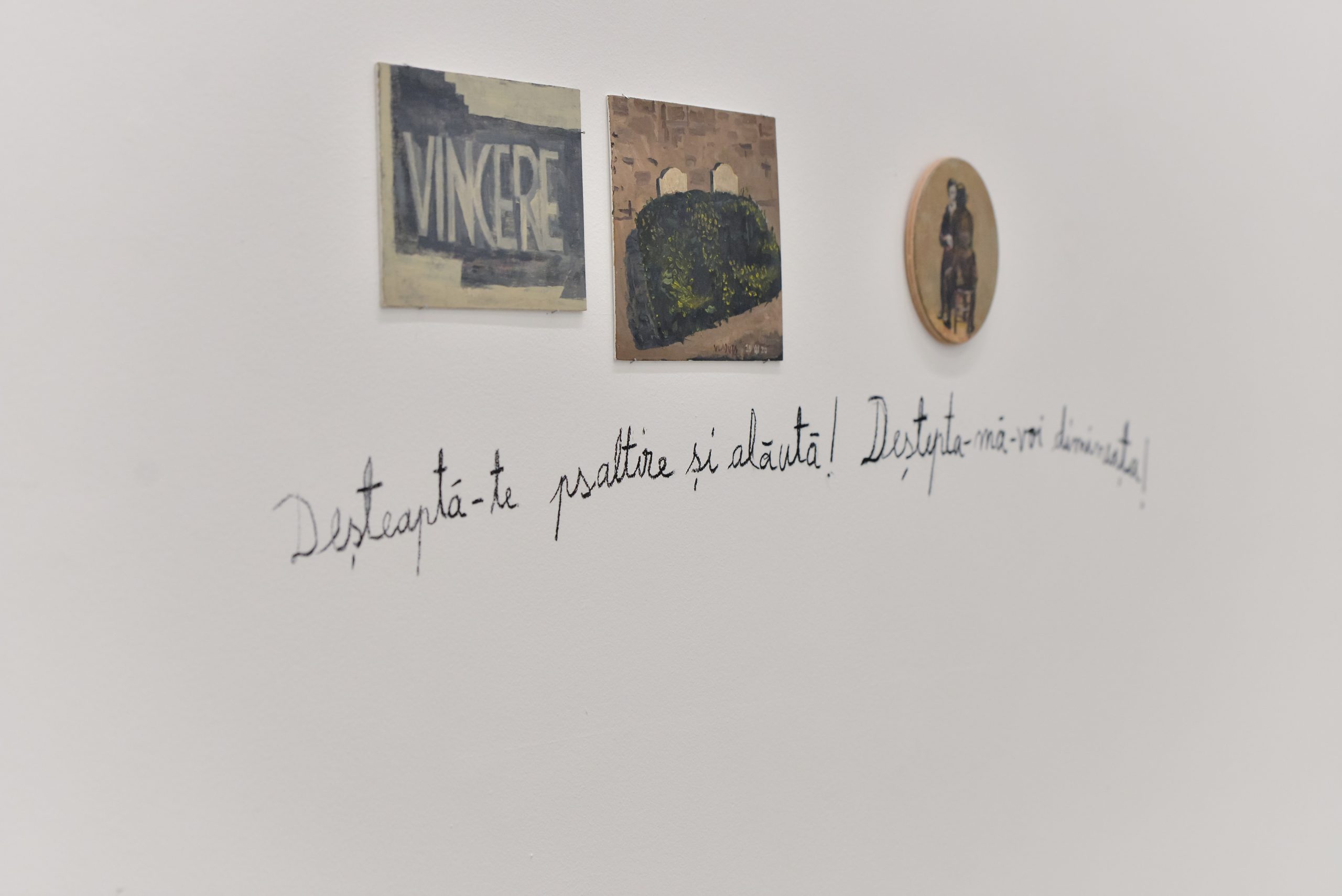

In the exhibition ‘WHEN I PAINT, I KNOW I WILL DIE! – A visual essay on Van Gogh’, artist Bogdan Vlăduță is facing his source of inspiration, the one who became his close companion, guide, and confidant – Vincent Van Gogh. In a visual but also written essay, Bogdan Vlăduță enters into a dialogue with the themes, methods, and symbols from Van Gogh’s work. The gallery space is restructured into a new visual territory that includes large works, installations, drawings, and in-situ interventions by the artist.

“This is neither a visual essay with exhaustive proposals nor a way to quickly analyze Van Gogh’s life, shedding the full light on unknown areas, ruining the mystery. It is not even a promise to take over the common understanding given by the world (to and) using Vincent’s drama.

Rather, my analysis advocates on acknowledging the weak and soft (or maybe defenseless?) part that lies in Vincent, the crumbs that fall far from the so-called great normative culture. Van Gogh possessed the ingredients for such a fragile painting. The miserable life, a failure following another failure, the awkwardness of social relations, the lack of worldly horizon, the cultivation of fatality, the despotic character, morality, the sense of the absolute, the desire to become “God’s poor man” as an apostle or a painter.

Van Gogh has the faith of a non-believer, of one who verifies everything by himself. His tools are painting, the human relations that left him scarred, his illnesses, and his escape from the confessional framework of Christianity – paradoxically, he discovers here, in an orthodox way and without even knowing it, the faith of the Eastern church.

I started my journey alongside Van Gogh in 2013 at the Musée d’Orsay in Paris. There, Van Gogh stands out from the rest with his unprecedented painting. At home, I share my findings with my close ones, including Sorin Dumitrescu.

Intrigued by my Parisian observations, master Dumitrescu answers with interest by writing me nine letters which made the subject of his book about the Dutch artist, and invites me to “remake” together Van Gogh’s Weaver at the loom as an attempt to interrogate the original work.

My paintings with Van Gogh are an exercise of undisguised admiration, made by one’s own means, where the slips combine with the virtues. The gain comes from my fellowship with Vincent, as I had access to the same muted values cultivated by the Dutchman and to the searchings which remained unanswered at that time but later became challenging as a “late bomb”. I was summoned to restrain myself and to fall under Vincent’s spell. He is my support, my crutch, the approval of the Way, but also the stake and the thorn, an ideal that does not give me peace but chaos, alteration, and anxiety.

My work is based on the observations that animated my master Sorin Dumitrescu, a painter that has the reflections of an icon painter, reflections which were also passed to me, a painter of the sensitive, with the impetuousness and vulnerability of personal endeavor. The acquired knowledge helped me to discover a way to the inherent eternal values and slowly fading virtues of the Dutch painter. From there, Vincent adds to my studio’s neuroses and strengths through a connection familiar to those artists who love their models. I think it’s appropriate to talk about “my Vincent” from now on.

About the Potato Eaters

There’s a Christian gasp in the traumatic painting of the Potato Eaters, an inner urge that presents the suffering of others and his own as a saving tool, worthy of being painted. There is an implicit act of his sacrifice for which I bow before him and kiss his feet. To be so fragile, yet to choose to paint vigorously, energetically. It looks like the painting of a man sentenced to death.

About non-colour

I chose to paint in black in order to illustrate the potato eaters, the boots, the old church tower in Nuenen and the cemetery, the faces of weavers, the self-portraits with old Vincent, the loom, and other paintings from the time of his debut. My paintings of Van Gogh are being drawn to me, a man shaped by the past and obsessed with it, with a penchant for drawing and the rhetoric of stable values. I strived to establish a model of coexistence with a crippled Van Gogh, a Vincent who burns creatively in the vicinity of death and who sees the Way while suffering. I have often wondered if Van Gogh would have liked my description.

About self-portraits

The painting with me impersonating Vincent preserves the vertical of older pictures in three quarters, with the same discrete deviation from the symmetrical plane, but it increases the power with which the details are represented. The head is bandaged, the left-hand makes an incomplete gesture and then disappears. The suppressed limb deeply heightens the hidden meaning and summons it to uncover itself more than the body as a whole does. Indiscernible, a curtain hangs and it’s being trampled on. More people are invited to participate in the painting. Van Gogh is reflected in the bandages on his face and the gestures that reveal the cause of his suffering, the injured ear. The curved, yellowish body reveals the Greek painter from Spain, El Greco. The portrait’s silhouette is emblematically accompanied by the presence of a ruin. A self-owned territory described in the context of Antiquity, of the beloved places and artifacts of history. “I have become like the owl of the ruins” he shouted!

About bones

I intended to paint something that included a lot of bones. The bone is a ruin of the body, a splendid artifact, and a clue for the Passage between worlds, but also the perfect engineering of the Creator. A structure for a design that encrypts the loss of the human being, but also the genome that can reconstruct it; through death and Resurrection, a back and forth grandly described in the vision of Ezekiel. The field of bones is the representation in which the landscape, described by each phalanx and cartilage, and propelled by the divine spirit, becomes the protagonist of the painting. The carpet with “whitened dry bones” is the mirror that reflects my face drawing the self-portrait, as a recall of the work from 2001, “When I paint I know I will die!”’

- Excerpt from the artist’s catalogue Bogdan Vlăduță Quand je peins, je sais que je vais mourir

The exhibition coincides with the much-awaited release of the artist’s catalog. The book includes the artist’s paintings, interviews, thoughts, and captions from his studio during the making process of the artworks.